| Greg's weights and measures |

| Greg's home page |

| Cooking main page |

| Recipe index |

| Cooking times |

| Noodle cooking times |

| Spice pastes |

| Weights and measures |

| Food suppliers |

| Greg's diary |

| Copyright info |

|

|

|

The success of any recipe depends on getting the quantities right. There are two main issues:

But how do you know what quantities to use? Simple: apply this rule:

Always weigh everything of importance.

And that's all. Nowadays you can buy digital scales for less than the price of a meal for four, and they're highly accurate, typically to 0.1%, far more accurate than needed. And ultimately the quantity you want is the weight, so why not measure that?

The problem is that there are dozens of different ways of measuring things, and your recipe will probably not include weights for everything. In the rest of this article I discuss some of the problems that this causes.

First, briefly, what's wrong with other methods?

Measuring things by volume works relatively well for liquids, and there's no real reason not to do so if you have the appropriate measuring vessels. But it's still not as accurate as weighing, for a number of reasons. Volumetric measures are always analogue, and the best you can get is about 1% accuracy. Consider measuring 40 ml of liquid with a 1 l measuring jug. The best you can get is about 5% accuracy. With a 1 kg digital scale, you can still get 0.25% accuracy.

Yes, it doesn't often make much difference, but why go to the trouble? Weighing is also usually faster. And if you want to be really pedantic, the volume of a liquid depends on the temperature.

Measuring solids with volumetric measure is a whole different kettle of fish. It bases on a number of tacit assumptions that may or may not be correct. More below.

We typically measure volume in cubic centimetres or derived quantities such as millilitres. In the USA and the UK they still use archaic measures like pints, quarts and gallons—in each case, with different volumes! And then there are cups and spoons, all of which can differ significantly. These differences are really enough to spoil your dish: if a dish wants, say, “½ tbsp salt”, it could be anywhere between 5.5 ml and 15 ml. If the writer of the recipe was thinking of the former, and you use the latter, you could spoil the dish. This is probably the main reason why recipes don't try to specify the exact amount of salt.

Finally, many recipes give counts: “3 cloves of garlic”. That's even worse, since the unit sizes can vary dramatically.

Just occasionally you'll see recipes which state quantities in terms of the cost of the ingredients. There's one below. This is particularly difficult.

This bases on an older version of this article, so some details may be duplicated.

Apart from the considerations above, in the majority of cases the quantities specified in cooking recipes are wrong. There seem to be two reasons for this:

The cooks cook first, and then later try to guess what they put in. In many cases they're badly wrong.

The quantities given are ambiguous or local. One of my favourites is in the Sarawak Salvation Army Boy's and Girl's Home Cookery Book, published in Kuching in 1968. The recipes are good, but this extract from a recipe for coconut shoot and chicken curry, by Wee Bee Siok, gives the idea:

| 1 | chicken weighing 2 to 3 katis (cut up) |

| 3 to 4 katis | coconut shoots |

| ... | |

| 5 sticks | lemon grass |

| 10 cts | ground or powdered turmeric |

A kati is a unit of weight that is obsolete even in Malaysia; it was 1⅓ lbs. “cts” is an abbreviation for “cents”: in other words, use the amount of turmeric that you could buy with MYR 0.10 in Kuching in 1968. At the time, it may have been helpful; nowadays it's just plain guesswork.

It's not only recipes from the end of Colonial Borneo that give you this kind of problem. Particularly English language recipes use units that are confusing to the point of uselessness. Here are some that particularly irritate me:

The law of Moses is probably the oldest well-known law that addresses this subject. Deuteronomy 25:14 states:

25:14 You shall not have in your house alternate measures, larger and smaller.

Clearly the background here is the use of the alternate weights for cheating others, but it doesn't say so in the law. So is this measuring jug illegal?

About the only reason I can find why it should not be is because it's only a single measure.

Many recipes specify volumes in “cups”. That's a very bad idea: The definitions of a “cup” differ by a factor of nearly three to one, depending on the country and the intention. Without knowing where your recipe has come from, you can't guess which one they meant. Also, “cups” as a cooking measurement are in general significantly larger than real cups. I've established that a cup can have at least one of the following volumes:

65 ml (a normal Italian Espresso cup).

84 ml (the “small cup” size on my coffee machine). I measured this from the scale on the side: this is the amount of water that goes into the machine. A few millilitres probably get lost in the brewing.

90 ml (another, ornate Espresso cup that I have).

100 ml (in the instructions of the coffee machine referred to above, “normal cups”). It's interesting to note that even the instructions diverge from the actual measurements on the device. The machine itself only measures “small cups” and “large cups”, so this must be referring to the 84 ml cups. Apart from that, these sizes seem to be standard misconception amongst coffee machine makers. I've never seen a cup to match, and I suspect it's so that they can sell a 6 cup coffee maker as a 12 cup device. This seems all the more plausible given that other coffee machines I've seen seem to have a “small” size of 100 ml.

105 ml (the “large cup” size on my coffee machine, as measured).

125 ml (in the same coffee machine instructions, “European cups”, presumably referring to the size that actually gives 105 ml). I've never seen a cup of this size, either.

150 ml, seen on a packet of Indian chicken tikka masala mix. From that image (“2 cups (300 ml)”), I thought they might have meant 300 ml per cup, but elsewhere they mention “3 cups (450 ml)”.

177 ml, the volume of a US coffee cup. I forgot to annotate this at the time, and I no longer know where I got it from.

180 ml, a Japanese “go”, used for measuring Sake and rice. It seems that this definition of “cup” is taking over in Australia too, though it's 28% less than the Australian “Metric cup”. In January 2009 I bought a rice cooker sold by ALDI Australia which uses this measurement. On 17 July 2011 David and Tuyết Yeardley got married, and one of the wedding presents was a rice cooker, this time from the Australian manufacturer Breville, and it came with a measuring cup which (by measurement) holds 180 ml at the brim. The scale itself only goes to 160 ml:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

200 ml, the Japanese cup. This is also the volume of a real tea or coffee cup, made in “Europe”. This bears a good relationship to the smaller coffee machine cups, unless the manufacturer lies: for every cup you want to drink, you select two in the coffee machine.

225 ml. I forget where this is, but I found it in one cookbook.

230 ml, a “normal "Standard Cup"” according to the Australian wheat producer Laucke, who observe that it's not the same as the “metric cup” (see below). They recommend not to use cups for measurement, so it's not clear why they have had to invent a new one.

236.6 ml, a “United States customary Cup” (about half a pint). Marked on a set of measures I have (see below).

238 ml, an “American Cup” (about half a pint). Noted in multiple cookbooks, though apparently not in any US statute. Maybe it's just an average of the other two.

240 ml, a “United States “legal” Cup” (about half a pint). Defined by law (§ 101.9 paragraph (b)(5)(viii)).

250 ml, an Australian “metric cup” (what an arrogant misnomer!).

265 ml, seen on an ALDI pasta machine measuring cup designed for flour. It's not immediately obvious, but in the second photo the cup is full almost to the brim with water:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

284 ml, a “British Cup” (half a pint). Noted in multiple cookbooks. This is a little more than the volume of a coffee mug, which I consider to be considerably larger than a “cup”. It's not very common, but it still crops up in many cookbooks. One example is the English translation of «La cuisine» by Jacqueline Gérard, published in 1980, which my daughter Yana showed me in September 2014. This book is also interesting because it implies 30 ml “tablespoons”.

350 ml, seen in this Australian cup (or is it disqualified as a mug?):

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

In order to avoid the water flooding from the under pan, you should add no more than 1800 ml (three cups).

So the biggest real cup that I know is 200 ml, and most cooking “cups” range between 235 and 285 ml. If you use a real cup as a measure, you'll almost certainly measure too little.

Despite all that, many cookbooks specify ingredients in “cups”, even when it's easier to weigh them. One reason might be that in the USA, the law (dated 1 April 2004, but presumably meant seriously) makes it the preferred form of measure:

(i) Cups, tablespoons, or teaspoons shall be used wherever possible

and appropriate except for beverages. For beverages, a manufacturer may

use fluid ounces.

And yes, the wording of that sentence is original, as I pulled it off the web site. My argument here is, of course, that it's never appropriate to use “cups” as a volumetric measure.

As noted above, even in the USA, the sizes aren't uniform. The same law defines a teaspoon as 5 ml and a cup as 240 ml; I've discovered measures which somehow found their way into my house in Australia, but appear to be an older US measure which equates a cup to 236.6 ml and a tablespoon to 14.79 ml:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Certainly not everybody has kitchen scales, but the inaccuracies inherent in misinterpreting “cups” are ridiculous, and even if you do guess correctly, you'd need multiple different cups to measure them. If you don't have scales, a direct volume (“300 ml” or “9 fl. oz.”) would be much less error-prone. The use of “cups” for cooking measures is a uniquely English language thing; none of my cookbooks in other languages use cups, and why should they? Given the potential inaccuracies, it's just plain stupid.

In the case I referred to, it would have been tempting to go for the Australian cup, since we're in Australia, but the package showed the weight in ounces, something that wouldn't happen here. In the end we made a toss-up between US and British, and went with 500 ml. That proved to be wrong: we had to add more water. I suppose we should have taken the British cups. But why does “Panni” do something that stupid? In the German version I'm sure they have the correct volumes.

Since I wrote this text, a page on this topic has been added to Wikipedia. I disagree with some of the opinions stated there, in particular that the differences are small enough to be disregarded, and many of the claims are not substantiated, but it has helped me update this page.

Many recipes also use terms like “teaspoon” (abbreviated tsp or teasp.) and “tablespoon” (usually abbreviated Tsp or tbsp., just to keep you on your toes). Some also use “dessertspoons” and sometimes abbreviate them “dessertsp.”. Again, their quantity varies; in addition, it's very difficult to find a spoon as big as the average “tablespoon”. It seems that, like the US measures, the Australian measures have some kind of official sanction, more's the pity. Maybe the others do too.

In addition, US legislation has two different values. The normal ones are 4.93 ml for a “teaspoon” and 14.79 ml for a “tablespoon”, but this Code of [US] Federal Regulations states (§ 101.9 Nutrition labeling of food, paragraph (b)(5)(viii)):

(viii) For nutrition labeling purposes, a teaspoon means 5 milliliters (mL), a tablespoon means 15 mL, a cup means 240 mL, 1 fl oz means 30 mL, and 1 oz in weight means 28 g.

In addition to all these, I know of at least one book, an English translation of «La cuisine» by Jacqueline Gérard, published in 1980, which my daughter Yana showed me in September 2014, which implies 30 ml “tablespoons”. It's possible that it also uses strange “teaspoons”.

On 5 October 2019 I read a further volume from Eve Shelby and Dan Pastuszczak: a UK tablespoon of 17.758 ml. I don't have any further indication of where this comes from, but it corresponds to ⅝ Imperial fluid ounce, so at least it fits into the scheme of things.

Here's a comparison of my measurements and “official” values:

| My | Australian | New Zealand | Gérard | |||||||||||

| Spoon | measured | (“metric”) | (“metric”) | UK | US | US label | ||||||||

| volume | standard | standard | ||||||||||||

| Petite cuillerée | 1.5 ml | |||||||||||||

| Teaspoon, kitchen | 2.5 - 4 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml | 4.93 ml | 5 ml | 5 ml | |||||||

| Teaspoon, serving | 4.5 ml | |||||||||||||

| Dessertspoon | 10 ml | |||||||||||||

| Tablespoon, serving | 11 ml | 20 ml | 15 ml | 15 ml | 14.79 ml | 15 ml | 30 ml | |||||||

| 17.758 ml | ||||||||||||||

| Tablespoon, large kitchen | 17 ml | |||||||||||||

My value for a « petite cuillerée » (French; see below) is a guess based on almost no information.

The important thing to note here is that the measures are usually smaller than you'd expect, in the case of Australian tablespoons nearly 50% less. Due to some accident, teaspoons are almost uniformly 5 ml (the US really does legislate both 4.93 ml and 5 ml, depending on intent), and other units in New Zealand, the UK and the US agree pretty closely with each other. But they don't agree with common utensils.

The other issue is that people, particularly in the USA, measure solids by volume. On 6 August 2020 I read a question on Quora: How many ounces are in a teaspoon of salt?. So I measured it with what I had in the kitchen The result: between 0.19 and 0.56 (avoirdupois) ounce.

In detail. Three different kinds of salt:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Take two different teaspoons, measure 10 “spoonfuls” of each kind of salt, and weigh them.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Here the average weight per spoonful:

| Salt kind | Spoon 1 | Spoon 2 | ||

| Rock salt | 7.55 g | 11.36 g | ||

| Kitchen salt | 7.51 g | 10.87 g | ||

| Table salt | 7.84 g | 9.98 g | ||

All these were done with naturally heaped teaspoons. Interestingly, and contrary to my expectations, the kind of salt didn't make a big difference to the weight: it's within experimental error (table salt was the heaviest from spoon 1, the lightest from spoon 2).

I also tried as level as possible a spoon (spoon 1) of table salt and got 5.35 g.

In the past I have tried to measure the volume of teaspoon 2 (level) and come up with a volume of about 3.5 ml. In the USA, a "teaspoon" is defined as 4.93 ml, in other countries 5 ml, all larger than any teaspoon I have measured.

The difference between definitely too little salt and definitely too much salt is probably about 30%. Here we have a difference of 300%. That's a perfect way to ruin a dish. And why?

On 13 March 2011 I discovered another example: a garden fungicide came with a measuring spoon which was supposed to contain 3 g of the product. In fact, I measured it at 7.5 g. That's really puzzling.

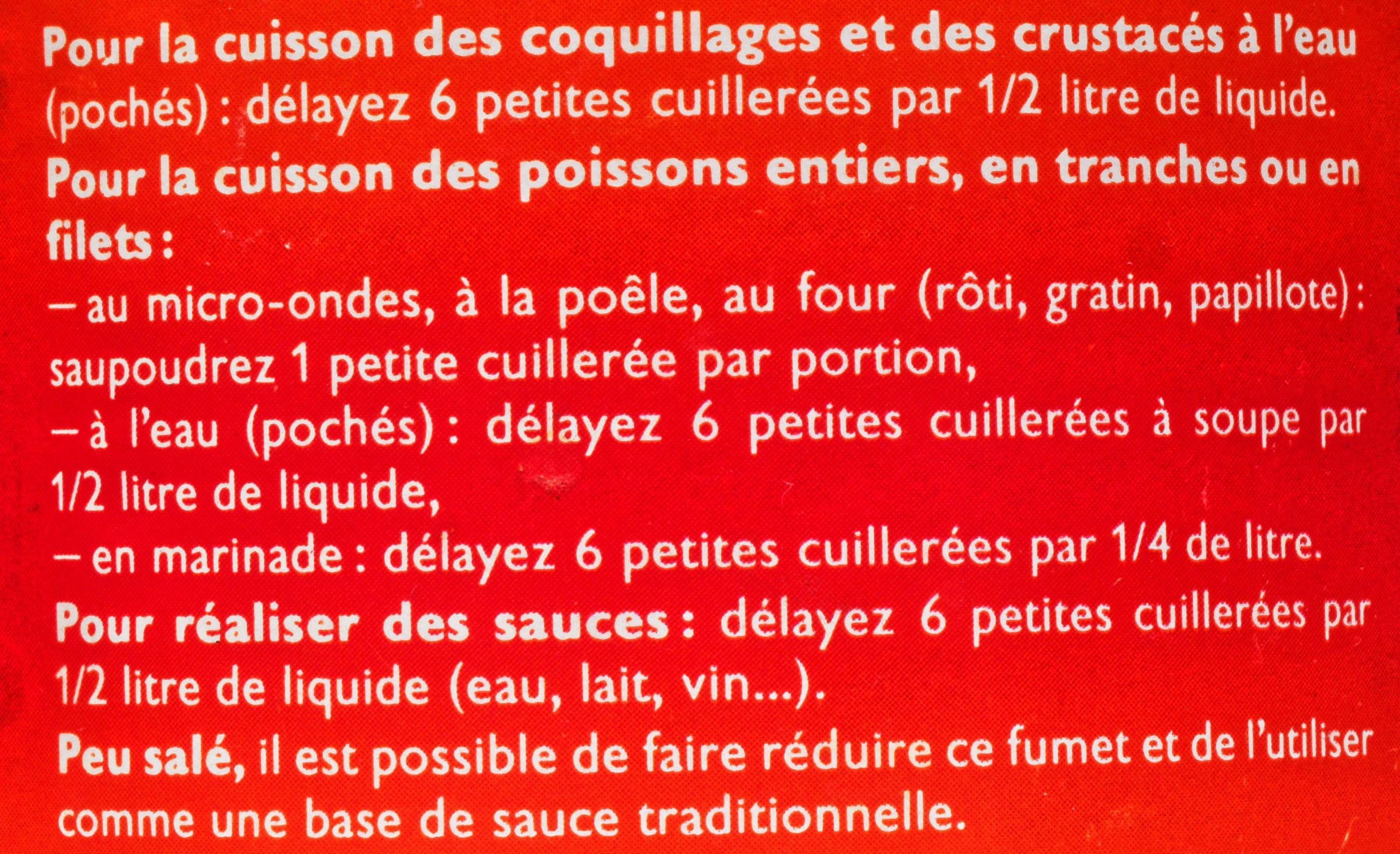

One exception to the “it must come from the USA” rule is this package of stock powder, sold apparently only in France, which I encountered on 6 June 2022:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

This calls for 6 « cuillerées » (little spoons) of powder per unit volume, either ¼ or ½ litre. There is absolutely no information about how big the spoons should be or what they should weigh, and French sources such as Wikipedia are also no help, though they do suggest that the smallest spoons have a volume of 2 ml. My guess of 1.5 ml is based on the quantities specified for other stock powders. On 28 April 2024 I established that, at least for this powder, a petite cuillerée weighs 2.5 g.

It's not enough to establish the volume of solids, of course: their shape can have considerable effect on the volume. For example: “1 tsp cloves, ground”. How much is that? If you take the tsp of cloves and then grind them, you won't get a tsp of ground cloves. Indeed, depending both on the shape of the tsp and the size of the cloves, the weight can vary considerably. But it's the weight that makes the difference, not the volume at some point during the processing.

In addition, measuring teaspoons is a very inaccurate business. Four “teaspoons”, measured with following measure, should be 19.72 ml. In fact, they're almost exactly 30 ml:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

That's 50% more than indicated.

To confuse things still more, the package of the coffee I drink (Melitta “German Premium”), as sold in Australia, recommends: “Use one heaped dessert spoon per cup, or vary according to taste”.

In Germany, there are special measuring spoons for coffee. They're intended to be used smooth (not heaped), and mine (which I presume to be relatively normal) has 22 ml. That's more than a “dessertspoon”, obviously. But how much more? That depends on the shape of the spoon and how high you can heap. Multiply that uncertainty by the uncertain size of a cup, and you can have between 10 ml and 22 ml of ground coffee in between 65 and 285 ml of liquid, a ratio of 10 to 1 in strength. That's ridiculous. About the best advice is “vary according to taste”. My own choice is one 22 ml German measuring spoon per 200 ml cup, or about 11% by volume.

Some recipes use terms like pints and quarts, units still official in the USA and in use in the UK. But how much are they? If you're cooking, it doesn't make any difference where you are: it's where the recipe comes from that counts. A US pint is 16 fluid ounces, or about 473 ml. An “imperial” pint is 20 fluid ounces, or about 568 ml. The issue is further confused by “conversion tables” which are more rules of thumb (“a pint is pretty much half a liter” or ”a pint is pretty much 0.6 litre”).

Don't believe that the fluid ounces are the same, either: they're closer than other measures, but there are still three of them. According to Wikipedia, the a British fluid ounce is 28.4130625 millilitres, and a US fluid ounce is 29.5735295625 millilitres. But for food labelling purposes, U.S. regulation 21 CFR 101.9(b)(5)(viii) allegedly defines a fluid ounce as 30 millilitres. None of this addresses the fact that a litre is an obsolete unit, and that they should mean cubic centimetres (and specify the temperature at which the measurement is to be done).

Note also that in Australia, where the pint is no longer an official unit of measure, the term is sometimes used for glasses of beer considerably smaller than the old Australian (Imperial) pint, even smaller than the US pint. If you're used to this measure, your guesswork could be significantly in error.

No matter what kind of pint you have, a quart is two of them, and a gallon is eight of them, always assuming you have the same kind of quart or gallon, of course.

Pedantically speaking, weights aren't important in cooking: what's important is the mass, and that's measured in grams and kilograms. The UK and US measures are ounces (28.35 grams), abbreviated oz., and pounds (16 oz or 453.6 g), abbreviated lb. The old Malaysian measure (see above) was katis and tahils. A tahil is 1 1/3 ounces, or 37.8 g; a kati is 16 tahils (1 1/3 lb, 604.8 g). That's not really too bad. The problem arises when you don't have any means of measuring weight or mass. The Americans are particularly good at weighing things in terms of cups (see above). The problem there is that the relationship between weight and volume depends on the material. You might measure rice in cups; measuring potatoes that way is completely ridiculous. Even in the case of rice, I'm sure that the relationship between weight and volume depends on the kind of rice.

| Cooking home page | Recipe index | Greg's home page | Greg's diary | Greg's photos |